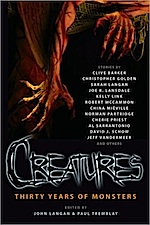

Presenting “Wishbones,” a story by Cherie Priest, reprinted from recent Prime Books horror anthology Creatures for Tor.com’s Monster Mash. In “Wishbones,” a horrific composite creature with a long-lived past spooks some locals….

At the Andersonville camp there is a great, stinking dread. The Confederates don’t have enough food of their own, so they sure as hell aren’t feeding their prisoners of war; and the prisoners who aren’t wasting away are dying of diseases faster than they can be replaced. Here, the world smells like bloody shit and coal smoke. It reeks of body odor and piss, and sweat.

South Georgia is nowhere to live by choice, and nowhere to die by starving.

The remains—the bodies of the ones who finally fell and couldn’t rise again—they lie in naked piles, leather over skeletons as thin as hat racks. They lie in stacks waiting to be put into the ground. They collect in the back buildings because no one is strong enough to dig anymore, not blue nor gray.

This does not explain why, at night and sometimes between the watches, the piles are shrinking.

Some of us thought, at first, how people were hungry enough that even the old meat-leather on the bones out back . . . it might be better than nothing. We talked amongst ourselves in riddles that rationalized unthinkable things. We wondered about our friends and fellow soldiers who were dead there, piled like cordwood. We said, of old Bill this—or old Frank that—how he’ d wish we weren’t so hungry, if he were still here. We agreed, we nodded our heads, and we thought about how we’ d make our secret ways back to the long, low shed.

But best as I know it, no one ever worked up the courage to do it. No one took any knives and crept back there, away from the guards who were half-starved themselves. How would we have cooked it, anyway? How do you smoke or carve a human being, an old friend?

Even so, the numbered dead began a backward count. One by one, the bodies went gone, and when fifteen or twenty had most definitely been taken, or lost, that’s when we began to hear the noise at night. It was hard to calculate, hard to pinpoint. Hard to explain, or indicate.

But it rattled like the bones of death himself, beneath a robe or within loose-hanging skin. It wobbled and clattered back behind the sheds where the dead were kept.

It walked. It crept.

It gathered.

“Pete’s Porno Palace, this is Scott, how can I help you?”

“Jesus,” Dean shook his head. “Pete is going to fire your ass one of these days.”

Scott wiggled the receiver next to his head and grinned. “Pizza Palace, ma’am. Of course that’s what I said. Best in Plains, don’t you know it? And what can I get for you today?”

“Jesus,” Dean mumbled again and walked away. He untied his apron and wadded it up around his hand, then left it on the counter. His cigarettes were in his jacket pocket, hanging by the back door.

He took the smokes and left the jacket. Dead of winter in south Georgia doesn’t usually call for anything heavier than a sweater, but sometimes when you own jackets, you just want to wear them—so you wait until it’s barely cold enough, and you drag them out anyway.

So the jacket stayed on the peg and Dean stepped outside.

Dark was coming, but not bad yet; and the backwoods pitch black would hold off for another hour at least. Even so, when he struck the wheel of the lighter the sparks were briefly blinding. Maybe it was darker already than he’d thought. Or maybe he should quit working double shifts, no matter how cute Lisa was, or how hard she swung her eyelashes at him when she asked him to cover for her.

He wrapped his lips around the cigarette and sucked it gently while the flame took hold. The bricks of the old pizza joint were almost warm against his back when he leaned there, beside the back door, facing the dumpster and the edge of the woods.

A crackling noise—small footsteps, or shuffling—rustled underneath the big metal trash container.

“Scram,” Dean commanded, but the soft crunching continued. He reached down by his feet and picked up the first thing he felt—an empty can that once held tomato sauce. He chucked it like a knuckleball and something squeaked, and scuttled.

“Stupid raccoons. Rats. Whatever.”

“One of these days,” Scott slipped through the doorway and shimmied sideways to stand next to him. “One of these days, it’s going to be a bear, and you’re going to get your face chewed off. Give me one?”

Dean palmed the pack to the delivery driver. “Help yourself. Bears. Stop shitting me. You ever see a bear out here?”

“No. But I’ve never seen a submarine, either, and I believe they exist in the world, someplace.”

“You do, huh?”

“Yeah. Seen pictures. Anyway, I’m just saying, and shit, it’s dark. We need to put a lamp out here or something. Can’t see a damn thing.” He lit a cigarette for himself and passed the pack back to Dean, who set it down on top of a crate.

“You got somewhere to go?”

Scott nodded. “Two large sausage and mushrooms. Going towards no man’s land, out towards Andersonville. Fucking hate that, driving out there.”

“Why?”

He popped his neck and sighed, taking another drag. “I always figure that’s where I’ll get a flat tire, or that’s where the transmission will finally drop out of the Civic. It’s only a matter of time, man, and I know my luck. It’ll happen there.”

“So what if it does? You’ve got a cell. I’d come and get you, or Pete would.”

“I don’t like it, is all. My sister’s boyfriend, you know Ben, he used to live out that way, and he talked about it like it was weird. You know. Because of the camp.”

Dean leaned his head back. “Oh yeah. The camp. I guess, sure. That could be weird. I think it’d be worse to live up north, near the battlefields. You hear cannons and artillery and shit. The camp was just . . . I don’t know. Jail for POWs. And it’s a park now. You seen it? It’s all pretty and mowed.”

“Man, people died there.”

“People die everywhere.” Dean crushed the cigarette against the wall, even though it was only half smoked.

Henry saw it first. He said he saw it, anyway. He said it was there, back by the sheds where they stored up the dried out dead until they could be dumped into a pit. According to him, it was a man-sized thing with black hole eyes and no soul inside it. According to him and his starved up brain, the thing moved all jerky, like it wasn’t used to having limbs. Like it wasn’t used to having legs, or feet, or nothing like that.

Like it was man-sized, but no man.

“It staggers,” Henry said. “It shuffles along and it takes them—it pulls them out the low windows, pulls them out in pieces and it, Jesus Lord, amen.”

“What’ d you see, anyway?” we asked, all gathered around close.

“It had an arm or something. A leg maybe. We get so skinny you can’t tell, by looking in the dark. You can’t see if that’s a hand or a foot on the end of it, just that it’s long and there’s a joint in the middle. But the thing I saw, it had a limb of some kind, and it didn’t bite it, didn’t eat it or anything like that. It peeled it, just like a banana. It used these white, long fingers to pick the skin and just strip it on down until there was nothing there but bone.”

The rest of us gasped, and one or two of us gagged.”Why?” I asked him.

“I haven’t the foggiest. I haven’t any idea, but that’s how it happened. That’s what it did. And then, when it finished yanking the skin away, it hugged on the bones what were left. It pulled them against its chest, and it’s like they stuck there. It’s like it pulled them against himself and they stayed there, and became part of him.”

“Why would it do something like that—and better still, what would do something like that? It doesn’t make any sense.”

“I don’t know,” he said, and he was shaking. “But I’ ll tell you this—I’ d gotten to thinking, these days, that maybe dying wasn’t the worst thing that could happen. You know how it is, here. You know how sometimes you see another one drop and you almost feel, for a few minutes, a little envy for him.”

“But not now,” I said.

“No, not now.”

“Lisa called in again,” Scott said, putting the phone down and looking like he wanted to swear. “Third time in two weeks. Remind me again why she’s still on the payroll? She’s not that hot.”

Dean shrugged into his apron and kept one eye on the cash register, where Lisa usually worked. “She’s been sick, I think. Something wrong with her. She’s been throwing up; I heard her in the bathroom a couple of days ago. That means we’re short again, right?”

“You’re not going to cover for her this time?”

“Can’t.” Dean adjusted the temperature dial on the side of the big pizza oven and felt a kick of heat when the old motor sparked to life.

“Can’t? Or won’t?”

“Whichever. I’ve got things to do tonight. I covered her with a double the last two times. You take this one.”

“No. And you can’t make me.”

“Well then, I guess they’ll be short tonight. It can’t always be my problem,” he complained, even though he knew why everyone acted like it was. He and Lisa had gone on a couple of dates once, and everyone treated them like it had been a secret office romance or something.

But Pete’s wasn’t an office, the dates hadn’t been secret, and there wasn’t anything much in the way of romance going on. Dean liked Lisa and he called her a friend, but it didn’t seem very mutual unless she couldn’t make it to work. He wondered if she was really sick and hiding it, like it was something worse than the flu.

The phone rang again as soon as Scott put it back on the hook.

“Christ,” he complained. “We don’t even open for another ten minutes. You answer it.”

“No. You get it. If it’s Lisa I don’t want to talk to her. She’ll try to rope me into covering for her, and I won’t do it.”

“Fine.” He lifted the phone and said, with his mouth too close to the receiver, “Pete’s Pizza Place, would you like to try two medium pizzas with two toppings for ten bucks?”

Dean walked away, back towards the refrigerator. He yanked the silvertone lever that opened the big walk-in; he stepped inside took the first two plastic cartons he found—green peppers, and onions, respectively. Both sliced. Whoever had closed had done a good job, he thought. Then he remembered that he hadn’t gone home until one in the morning, and that the handiwork was his own.

“I’m here too damn much,” he said to the olives. The olives didn’t answer, but they implied their agreement by floating merrily in their own juices.

He stacked the olives on top of the green peppers and onions so that the three containers fit beneath his chin. With his hip, he opened the door again and carried the toppings out to the set-up counter and began to lay them out.

“Fucking A,” Scott swore, still scribbling something down on the order pad kept next to the phone. “Another one.”

“Another one what?”

“Another delivery, all the way out in Andersonville.”

“That’s not that far.”

“Yeah, well. You know why I don’t like it.”

Dean cocked his head, dropping the olives into their usual spot with a sliding click. “Because you’re a superstitious bastard?”

“That is correct, sir. It’s the same house, I think. I told the guy he couldn’t have his order for another hour at least, but he didn’t care. So. Fine, I guess. I’ll drive it out once we finally get open, and at least it’s still daylight. Where’s Pete?”

“He’s not coming in until noon. He’ll be here then, though.”

“Okay. Cool. So it’s just us until then?”

“Yep.” Dean abandoned the conversation for the refrigerator again. This time he emerged with crumbly sausage balls and a fat sliced stack of pepperoni. He wasn’t concerned about the lack of help; they’d opened the store alone before, and it wasn’t too bad.

“I thought I heard someone out back, a few minutes ago. I thought maybe it was Lisa, but I don’t know why.”

“Lisa just called in, though.”

“Yeah, I know. I don’t know why I thought it was her. It turned out to be nobody, I guess.” He stopped talking there, even though it sounded like he wanted to say more.

Dean dropped the pepperoni rounds into their appropriate spot and wiped a little bit of grease on his apron. “Out back? By the dumpster?”

“Yeah.”

“Maybe it was a bear.”

“You’re an asshole. It wasn’t a bear.”

“It wasn’t Lisa, either.”

“Smelled like her.”

Dean frowned. “What?”

“It smelled like her, I think that’s what it was.” Scott tweaked the pen and the order pad between his hands and leaned back against the counter. “She wears that rose perfume sometimes, she puts it in her hair.”

“How often do you get close enough to tell?”

Scott slapped the order pad against the counter and left it there. “You know what I mean—she wears it strong because she doesn’t want her mom to know she smokes. You can smell it in the back, in the kitchen, when she goes through there to take a break.”

“I know what you mean, yeah. Okay.”

“Well, that’s it. That’s what I smelled. But she wasn’t there.”

“Nobody was there.”

“That’s what I said. Nobody was there. But I felt like someone was watching me.”

Dean raised an eyebrow that didn’t care one way or another, and went back towards the refrigerator for another armload of toppings. “Must’ve been that goddamn mythical bear.”

The thing out back, behind the sheds, it’s getting bigger. Charles has seen it now, and the Sergeant too—they both say it’s bigger than a man, and either Henry’s been lying or the thing is getting bigger.

We talk about it more than we should, maybe. But there’s nothing else to talk about, except how we want to go home and how much we’ d love a meal. So we tell each other about the thing like it’s a campfire story, as if we’re little boys trying to scare each other. Except we don’t want to anymore, really. We’re scared enough already, and now we’re just trying to understand what new, fresh horror has been imposed upon us.

As if this were not enough.

We are all so hungry, and we know there’s no prayer for food since our captors haven’t got any either, even for themselves. If the guards can’t feed themselves, then we prisoners are done for.

In our bunks, smelling like summer in a charnel house, we gather and talk and wait. At night, we cluster close together even though all of us stink of death and bodies that haven’t seen a bath in months. It’s better than cowering alone and listening to the knock-kneed haint come walking by.

We think it grows by consuming us—it eats the starved ones up and walks on borrowed bones ill-fit together. And so many of us have wasted away, and so many more are bound to follow.

In another month, that thing will be a god.

“Hey,” Lisa said. Her long brown hair was tied back behind her ears, elfstyle, and her eyes were more bloodshot than blue.

Dean thought maybe she was looking thinner every day, like her collarbones jutted sharper out of her tank top and maybe her tits were settling closer to her ribcage. “Hey. Welcome back.”

“Sure,” she said, but it didn’t make much sense as a response.

At supper rush she manned the cash register at the end of the counter, and Scott leaned in over Dean’s shoulder. “She looks like hell.”

“Yeah she does. Told you. She’s been sick.”

“That doesn’t look like sick to me, exactly.”

Dean shifted his arms to push Scott back, out of his personal space.

“What do you think it looks like, then? What are you saying? You think it’s drugs or something?”

“You said it, not me. It looks like it, though. Look at her. And you know what—she’s gone to the bathroom three times in the last five hours.”

“You’ve been counting? That’s fucked up, man.”

“I’ve been counting because I’ve been covering the register while you’ve been making pizzas. It’s not like I’ve been taking inventory of her bladder or anything.” He tapped his foot against the counter’s support and chewed his lower lip. “I’m thinking, it could be crystal meth, or something like that. Meth makes you skinny.”

“Meth makes you wired too,” Dean argued. “She’s been dragging. I think she’s just been sick. I wonder if, do you think it’s something like cancer? Christ, what if she has AIDS or something?”

“Did you ever fuck her?”

“No. Didn’t go together that long.”

Scott raised a shoulder and crushed his lips together in a dismissive grimace. “Then who cares?”

“I do, sort of. She’s all right. Don’t be an asshole about her. Hey—the phone’s ringing. It’s for you.”

“I don’t want to answer it.”

“Well, you’re going to.” Dean turned his back completely, absorbing himself in the scattering of green things onto the crust and paste.

After a few seconds of being ignored, Scott took the hint and picked up the phone. “Pete’s Party Palace, what’s your request?”

Dean returned to making pizzas and shoveling them onto the slow-moving conveyor belt in the oven. Lisa stayed at the register and didn’t seem to notice much of anything that wasn’t right in front of her.

He watched, though. He waited for her to take a break, and then he followed her—back outside to where the dumpsters are pillaged by the creatures who come up from the edge of the woods.

By the time he reached the doorway she was struggling with a cigarette lighter, so he offered her his.

“Thanks,” she said, and she leaned against the bricks.

Dean joined her. “I’ve been wanting to ask you,” he started, but she cut him off.

“Thanks for covering for me the other night. I appreciated it. I wasn’t feeling good, is all.”

“That’s cool. No big deal. I wanted to ask you, though, if something’s wrong. I mean, really wrong. I know we’re not that tight or anything, but if you need something, all you have to do is say so.”

Lisa took a short drag on the cigarette, one that couldn’t have earned her much nicotine. “What are you trying to ask me? You talking your way around something?”

He studied her closely, trying to think of how to ask what he meant. She was shaky—not in a hard way like she was shivering, but in a low-grade hum that meant her whole body was moving, very slightly.

When her fingers squeezed themselves around the cigarette, her chipped pearl nail polish looked ill and yellow against the paper. She glared out at the dumpster, and out past it. She glared into the coming dark like it might tell her important things, but she didn’t really expect it to.

“Are you sick? I can’t ask it any better than that. You’ve looked, I mean, you haven’t looked good the last few times you’ve been here. Like you’re weak, or like you’ve got a fever. I was wondering if maybe there wasn’t something really wrong and you hadn’t felt like telling us.”

“Like what?”

“Like, I don’t know. Cancer or something.” He didn’t mention Scott’s meth theory because it seemed even ruder than telling a girl she looked terrible. He rolled on his shoulder to face her. “Look, you—you look like you’re wasting away. You’ve been losing weight, enough weight that Scott even noticed, and he didn’t notice it when you cut your hair off and dyed it black last year. It’s pretty dramatic.”

It was strange and not at all pleasant, the small smile that lifted a corner of her mouth beside the cigarette. “Bless your heart,” she breathed. Then, a little louder, “You think I’m shrinking? You didn’t have to say it like you were asking if I was dying. Most women like it if you point out they’re losing weight.”

“Yeah, but . . . ” he couldn’t figure out a tactful way to phrase the obvious rest.

“It’s been good, lately. I’ve been getting into clothes I haven’t worn since junior high.”

“That’s good?”

“It might be. I think it’s good. I could still stand to—” she stopped herself, and changed her mind. “It’s not the end of the world, dropping a few pounds. It’s a good thing. I don’t mind it, and I wish I could take another few down, so stop worrying. That’s all it is. I’m on a diet.”

“What kind of diet? Like a starvation diet, or what? You got some kind of eating disorder now, is that how it is?”

“There’s nothing disordered about it. It’s the most orderly thing I’ve ever done.” She crushed the lit end of the cigarette against the wall, leaving a black streak on the brick and a mangled butt on the ground as she went back inside.

There’s a Chinaman here in camp, a small fellow who looks like he might be a thousand years old. Someone told me he came from out west, out across the frontier—someone said he’ d come east from California, but I can’t imagine why.

He says he’s no Chinaman, and he seems to get offended if you call him one, even though I don’t think he understands one word of English out of three.

I don’t know his name or what he’s doing here, except that he runs errands between the officers. He washes pots and clothes for the Confederates when there’s water to wash them, and I guess that’s not strange since there aren’t any women around.

The little old fellow is mostly quiet. He mostly listens and keeps his head low, not wanting to draw any attention to himself. Henry says he looks strange and wise, and I don’t know if that’s right or not, but the Chinaman sure has these black, sharp eyes that always seem to know something.

He came up on us, the other night while we were talking about the thing that eats the bones out back. Like I told it, I don’t know how much of our talk he understands—but he got the idea. He saw our fear, and he watched the way we pointed and whispered at the sheds out back.

One of the guards heard us too, and he told us to shut ourselves up and be quiet, we were just trying to start trouble. He was complaining how we didn’t need any more trouble than we’ d already got, and he was right, but that didn’t change anything.

When he was gone, the Chinaman approached us with small steps and a hunched back that bowed when he tiptoed forward. He nodded, yes. He nodded like he understood. He pointed one long, wrinkled finger towards the sheds where the dead are stored and where they wait to be buried.

“Gashadokuro,” he said. It was a funny, long word filled with sharp edges.

We stared up at him, blank faces not comprehending very well. He looked back at us, frustrated that he could not make us comprehend. “Gashadokuro,” he said again, pointing harder.

And then I nodded, trying to repeat the piece of foreign tongue and probably mangling it past recognition. I tried to convey my realization, that yes—the thing was there, and yes—it had a name, and it was a foreign name from across the country, and across the ocean, because white men like us wouldn’t know what to call it.

Gashadokuro.

We can’t even say it.

After Lisa was gone, Dean kept smoking and he said to the empty back lot, “You don’t eat with us anymore. We all used to eat together after shift.”

A creak answered him, with a twisting squeal of metal and a gentle knocking.

He jumped, and settled. The dumpster again. Something inside it. No, something behind it. Dean held his dwindling cigarette out like a weapon, or a pointer.

“Scram,” he said, but he didn’t say it loud. “Scram, you goddamn rats. Raccoons.” It wasn’t worth adding “bears” to the list, because he still thought Scott was full of shit.

But it was dark enough, and the woods were a black line of soldier-straight trees, hiding everything beyond or past them. He stepped forward, just a pace or two. Towards the dumpster, and the rattling shuffle that came from behind it, or beside it—somewhere near it.

“Get lost,” he said with a touch more volume as another possibility occurred to him. Plains didn’t have too many homeless people; it didn’t have too many people of any sort, truth to tell. But there was always the chance of a passing human scavenger. You never knew, in this day and age.

The noise was louder as he got closer—tracking it with his ears to a spot behind the dumpster, close to the trees. It wasn’t all scratching, either. It was something muffled and banging together—something like pool balls clattering in felt, or inside a leather bag. He couldn’t pinpoint it, no matter how hard he listened.

Scott’s head popped into the doorway, casting a giant round shadow against Dean’s back. “Who’re you talking to out here? Yourself again?”

“Sure.” He turned and squinted at the doorway, where the world suddenly looked much brighter within that rectangle.

“I’ve got to make another run out to my favorite spot in all of Georgia. You coming back inside or what? I can’t leave until someone takes the ovens, and baby, that needs to be you.”

Dean looked back into the woods, past the dumpster where the noise had stopped as soon as Scott appeared. “Back towards the old prison camp?”

“Of course. Why can’t that guy always call during the day, huh? Why’s he got to wait until the creeps come out?”

“Why would you put it that way?” Dean asked, a hint of petulance framing the words. “There aren’t any creeps. There’s just the old camp, and there’s nothing there anymore.”

“Then why don’t you drive it, if you’re so fucking unperturbable. I hate going out there, it’s—”

“It’s not even two miles, you chickenshit. You could practically walk them the pizza in the time you’ve stood here complaining about it.”

“Practically, but never. I’m serious. You do it, if that’s what it’s about. I’ll take the ovens and the onion-smelling hands for a few minutes. You go brave the ghosts from the old camp.”

“I will, then. Fine. Give me the address.” He pulled himself back inside and swiped the sheet of paper out of Scott’s hand.

The gash-beast is hungry; it is as hungry as we are. As it grows, so does its appetite. As it grows, and we diminish, it becomes ravenous. It outpaces us.

For us, the hunger comes and goes—and comes again.

It’s when it comes again that we know, we know that it won’t be dysentery or cholera or pneumonia that takes us. We know it will be the hunger. When first we go without food the days drag and stretch, and the belly is all we can think of. But in a few days, after a week or so, the hunger fades. The body adjusts. The stomach shrinks and thoughts of food are sharply sweet, but no longer dire.

It when the hunger comes again that we know.

It takes some time—maybe a month, maybe less. But when the weeks have slid by and there’s nothing yet to fill us, when the hunger returns it returns with a message: “Now,” it says, “you are dying. Now your body consumes itself from the inside, out. This is what will kill you.”

The gash-monster knows. It hovers close, a clattering angel of death that follows the weakest ones after dark. It hums and taps, drumming its bone-fingers against the walls and waiting by the doors. It is impatient. And we are all afraid, even those of us whose stomachs have balled themselves into tight little knots that don’t cry out just yet—we are all afraid that the gash-monster’s impatience will get the better of it.

We are all afraid that the time will come when the dead aren’t quite enough, and it comes to chase the living, starving, withering souls whose hearts still beat with a feeble persistence.

We are all afraid that the time will come when it pulls our still-living limbs apart, and peels our skin away, and eats our bones while we bleed and cry on the ground.

We keep ourselves quiet when the hunger returns.

We do not want it to hear us.

When Dean returned, he reclaimed his apron and went back to the pizza line. “Hey look,” he told Scott. “Nothing snuck up and ate me.”

“Bite me, big boy. Speaking of eating, we’re shutting down in ten—no, eight minutes, and there are two large leftovers with our names on ’em. Pete said they’re ours if we want them.”

“Good to know. What’s on them?”

“Gross shit. Pineapples and onion on the one, and sausage, chicken and anchovy on the other—that’s your three major meat groups, right there. Three of the four, anyway. It’d need hamburger too, to make a good square meal of meat.”

“Jesus.” Dean made a face.

Scott mirrored the grimace and put the pizzas on the outside edge of the oven to stay warm. “Yeah. If I weren’t so hungry, I’d leave them out back for the bears, but I’ve been here since before lunch and I’m either going to eat one of these fuckers, or my own hand—whichever holds still first and longest. Lisa—hey string bean there—we’ll save some for you, baby. You could stand a little grease on those bones. It’ll fatten you up. Put hair on your chest.”

Lisa pushed a button on the cash register to open the drawer. “You don’t know a damn thing about women, do you Scott?”

“Probably not. Anyway, you want some?”

She reached beneath the drawer and scooped out the twenties, gathering them into a little stack. “No.”

Dean watched her count for a few seconds, then said, “You didn’t take a break for supper.”

“So?”

“So you’ve been here as long as the rest of us. And you’re not starving?”

“No. Mind your own business. No, I’m not starving.”

She went back to her counting, and made a point of not paying any further attention to either of the other closers. When she wrapped up the drawer’s contents, she put a rubber band around them and slipped them into a zippered bag that she then deposited into the safe.

“Aren’t you jumping the gun a tad with that?” Dean asked, but she shrugged back at him.

“There’s nobody here. Who cares? Turn off the sign. Let’s close up.”

“Where are you going?”

“Bathroom, to change clothes. I’m not walking home smelling like this. It’s gross.”

Dean took a rag and started wiping down the pizza line. “Smelling like food? It’s not the grossest thing in the world, not by a long shot.”

“I don’t like it,” she said. She lifted up the counter blocker that kept customers from wandering back into the kitchen and it almost looked like too much effort for those bird-frail arms. She shuddered when it dropped it back down behind her, when it fell back to its slot with a clang.

“Lisa?” Dean asked, thinking maybe he’d follow her or ask more questions, but she saw it coming and she waved him away.

“Don’t,” she ordered. “Just . . . don’t.”

“Stick around a few minutes, I’ll drive you home when we’re finished eating. I’ll give you a lift—I mean, you really don’t look like you’re in any shape to walk back to the ‘burbs.”

“I’m in plenty good shape to walk anywhere I want. Thanks, though.” She added the last part as she rounded the corner, taking a backpack with her. The bathroom door clicked itself shut behind her.

Dean jerked his hands into the air. “I give up,” he declared.

“It’s about time,” Scott said. The words were already muffled around a mouth full of pizza. “Come and get it. More for us.”

“Okay. Yeah, okay.”

The back door was open, propped that way for the sake of air flow. Dean went back through the kitchen, back beside the refrigerator, and back to that open door that looked out over the empty lot—and the woods beyond it.

Scott was right. They needed a lamp.

The dumpster loomed black before the lot. It stank of rust, rot, and the decay of uneaten things that should’ve long ago been picked up. Trash service was spotty out there sometimes, and the bin was starting to fill. Maybe the collectors would come by before the morning.

It was as good an excuse as any not to take out the trash.

A clatter popped, loud beside his head.

Dean jerked—staring around and trying not to look too frantic, in case it was just Scott being an asshole. But Scott was inside, he could hear him. He’d turned up the radio past the point of ambient noise; and he’d tuned it to a louder station than Pete ever subjected the customers to. Inside, Scott was singing along to Skinny Puppy with his mouth full.

The clatter wasn’t Scott.

It was hard to place, like before—hard to tell exactly where the sound was, or exactly what it sounded like. It sounded so close to so many things, but not precisely like any of them. The clicking was loud but muffled. Next to his head, between the building and the dumpster, and high. Up higher, he thought, higher than the edge of the window sill were the pattering knocks when they sounded again.

“Is somebody out here?” Dean asked, not loud enough to even pretend he wanted a response.

The clattering continued, high and muffled, and rhythmic—there was a balance to it, a swinging, swaying, like the pendulum on a large clock moving back and forth. Or like hips, loosely jointed and walking in lanky-legged steps.

“I . . . ” There should’ve been more to say, but the noise—all rounded edges and heavy bones—was only coming closer.

He retreated back into the doorway, still seeing nothing except, maybe, at the edge of his sight something pale in a jagged flash. Whatever it was, he wanted no more of it; he tumbled over himself to get back inside, and he shut the door fast—hard. He drew the bolt back and stepped away, staring down at the door’s lever handle, waiting for it to wiggle or slide.

“Dude?” Scott called. “Something wrong? You’re panting like a sick dog in here; I can hear you all the way in the kitchen.”

“I’m not panting!” Dean all but shouted, and as he objected he could hear his own breath dragging unevenly from his chest and out his mouth. “I’m not—there was something outside. Don’t look at me like that, I’m serious. There’s something out there and it’s not a goddamn bear.”

“Okay, calm down. What, then? Another raccoon or rat?”

“Fuck off, man. I don’t know what. I don’t know what, but I’m not going back to look.”

“Let me see,” he said but it was less a request than an announcement that he was going to look outside.

“Don’t,” Dean commanded, stepping between his coworker and the bolted metal door. “Don’t. Whatever it was, we don’t want it in here. It was, it was big—and I don’t know what. Just leave it shut. It’ll go away, later.”

“You’re actually scared?”

“Yes, I’m scared. What is there—there’s rabies and shit, man. And big things with big teeth in the woods. Fine, a bear, if you want to call it that—if you want to wonder or worry about that.”

Scott snorted. “Puss.”

“Less a puss than you, motherfucker. At least I’m afraid of actual things, and not ghosts, like dead people from the Civil War. That ain’t a ghost out there, whatever it is. It’s something that came in from the woods, is what. And I’d just as soon not get eaten on the way home from work, so leave the door closed or you’ll let it in.”

“Fine,” Scott held out his hands in surrender. “Fine, Christ. If it’s that big a deal to you. Calm down, already. Don’t get crazy.”

“I’m not crazy, I think I’ve heard it out there before,” he said, and he realized as the words came out that he was serious—he had heard it before, but not so loud and not so close.

It had been working itself up, working itself close. Homing in.

Dean shuddered, and peeled his apron off. He tossed it at the pegs where the coats were usually kept and it stuck, then straggled itself down to the floor. “Forget it. I’m not hungry anymore. I’m going home.”

“With the monster outside? Ooh, you’re brave.”

“I’m going out the front,” Dean growled. “Where there’s a nice open parking lot and a big ol’ streetlamp.”

“Before you go—are you giving Lisa a ride? I think she needs one.”

“What? She said no. She said she didn’t want one.”

Scott cocked his head towards the front of the restaurant, in the vague, general direction of the bathrooms. “She’s still in the bathroom. Don’t leave her with me; she’s not my problem.”

“Not mine either.”

“You care more than I do. Go knock on the door or something.”

Dean stood still and scowled, weighing the options and his own worry. “Fine. I’ll go get her.”

If nothing else, it gave him something else to think about; it gave him a few more seconds to calm his heartbeat and another problem to think about. He grabbed his light coat and shifted his shoulders into it, then pulled his keys out of his jeans pocket and went to the door of the ladies room.

He pressed his head against it, listening for any signs of life within. He rapped the back of his knuckles against the wood, lightly—politely. “Hey Lisa. You in there, still?”

She didn’t answer, so he knocked again.

“You in there? Hey, I’m going home now. I’m tired and I’m not as hungry as I thought I was. Open up. I’ll give you a ride home. Hey. Are you in there?” He knew she must be, but there was no hint of life. No water running, no toilets flushing. Again he knocked, but there wasn’t any answer. “Do you need help? You’d better say something, or else I’m going to come in there. Do you hear me?”

Nothing.

Until there was the crash.

The sound of splintering, shattering glass rang out behind the closed door, jolting Dean so badly he leaped away. “Lisa?” he shouted, and he reached for the knob. It moved a click left and right, but didn’t open. “Lisa?”

Scott came tearing around through the dining area. “Did you hear that? What was that?”

“In there—” Dean pointed at the locked door. “It came from inside the bathroom. The thing outside, I think it’s gotten in—that’s all I can think of,” he trailed off, kicking at the door. Glass wasn’t breaking anymore, but it was being pushed around—scraped around, and yes, there was that tell-tale knocking, rattling, clapping together of hard things with worn edges. He could hear it through the door.

“What’s that sound in there?”

“Same sound I heard outside.”

“Well, what is it?” Scott’s voice was rising, creeping up towards shrill as the ruckus in the bathroom continued and the clacking rattles filled more and more of the space inside the restaurant. “What’s that crazy sound?”

“I told you, I don’t know!” Dean retreated a few feet and slammed himself forward, hip against the door. Something splintered, but nothing broke. He did it again, and motioned for Scott to join him. “Lisa, what’s going on in there? Lisa?”

Nothing and no one answered, so the guys pushed together and then, when both their bodies met the wood at once, the door caved in and they caved in after it—tumbling forward and slipping on cool tiles.

“Lisa?” they said together.

“Lisa?” Dean asked again, but the bathroom was empty and there was no sound at all—not even the running of a commode out of order, or the whistle of warm January wind through the broken glass of the small square window.

“Could she—could she have gotten through there? Through that?” Scott asked, now as breathless as Dean and just as confused. He meant the window, all smashed and hanging open. It wasn’t meant for escaping, or anything half so glamorous. It was installed for ventilation, or for light. It was too small for a normal-sized woman to fit through, or climb through.

But Dean could still hear, in his head more than in the night, the smattering beats of the knobby creature that crouched in the dark beyond the dumpster.

He climbed up onto counter, stepping past the sink and prying himself up high to see out the window. A hulking shape all corners and shadows was walking, retreating, removing itself from the restaurant.

It stopped.

It halted like it had snagged itself on something. It swiveled an oversized head on a twig-thin neck, and it lifted its face to gaze at the window from which Dean watched.

Not one head, but many together. Not one thing, but parts of a hundred—a thousand others. A skull made of skulls, ribs made of ribs, it was fleshless and breathless. Its ivory limbs quivered together, chattering a low-frequency buzz of bone on bone, dangling loose from unfinished joints.

Dean’s breath caught in his throat.

The thing turned away. It loped slowly towards the trees, into the woods. It wandered into the sheltering darkness of the park, towards the old camp at Andersonville.

“Wishbones” copyright © 2011 Cherie Priest

Creepy . . .

OMG!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

The story left me going O.O It was great! Cherie Priest is a fantastic author, and I hope more of her reprints appear on Tor.com soon!

Seconded, on all counts! Good stuff. It’s hard to get truly creeped out while reading at work, stuck in a cubicle under a bunch of fluorescent lights, but yeah, this one did it for me.

She tries too hard with using the f-word in this story; this is coming from someone who the f-bomb comes naturally and I had submitted Gruesome Cargo II for TOR.com a few years back. The rejection letter I got was downright priceless. Sorry Cherie go back to writing steampunk because you try to hard at doing the hard rough style; it comes natural to me and seeing monsters from reality like what unfolded at Wheaton College. This is coming from someone who had seen her beginnings and reading this story.

Well I have a much stronger work called The Truth Teller and Blackened Horror Reality. I published a much stronger author than this in Carol Sullivan as she wrote the story Fat Busters — she went for a taboo; cannibalism. The most hardcore story ever written from the female horror authors and she did it in the pages of The Ethereal Gazette. When I get the Tabloid Purposes anthologies back online you will see other examples from the lady authors. Issue Five has a strong example in the short story called The Other David — this roster rocked it as I will give you the name of that author Cheryl McCleary who was one of the Class of 1994 hopefuls who became part of The Gazette.

The Lost Souls by Sarah Williams is a killer story too if you guys need to check out some of the lady authors on my roster over the years. They are not slouches though Cherie Priest won’t give them the time of day. Joline Lieck from the first namesake (first cycle) and Fatima Stephens from the reboot cycle really kicked some ass too.